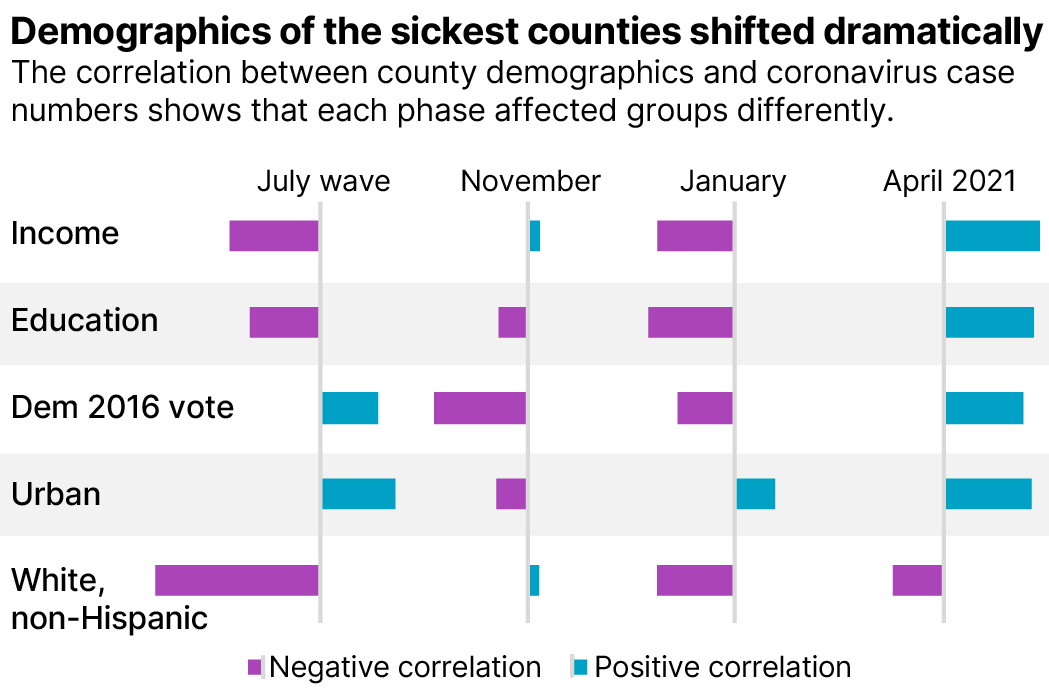

Coronavirus cases in the U.S. were again on the rise last month, tempering the hope that we were nearing the end of the pandemic, despite wider availability of vaccines. While this spring’s bump — aided by fast-spreading variants — was much smaller than the spike in cases in January, it surpassed the peaks of previous surges in November and July. The demographics of the sickest counties last month stand out in stark contrast to those in previous phases of the outbreak and could reflect changing behaviors among those who had previously been more diligent with social distancing and other preventative measures.

In a race against variants, about a third the population has been fully vaccinated. The inoculations are having a noticeable impact on illness, especially among older adults — three quarters of whom have been fully vaccinated. Amid these changes, April’s surge was also the first to have a larger effect on more educated counties and a significantly higher impact on more wealthy counties.

The underlying reasons for the change in demographics in April’s wave appear a bit more complex than in previous surges. April cases were higher in counties where people had recently changed their level of certain activities, based on an analysis of anonymized cell phone data from SafeGraph. There was a significant correlation between higher cases and visits to grade schools that had increased between January and April. There was also a correlation between sicker counties and trips to restaurants, bars and preschools. The sickest counties were not necessarily those with the most travel but where the levels of travel had increased the most between January and April.

An analysis using data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Census Bureau shows that each pandemic surge period brought the most severe impacts to specific groups:

April 2021

January 2021

November 2020

July 2020

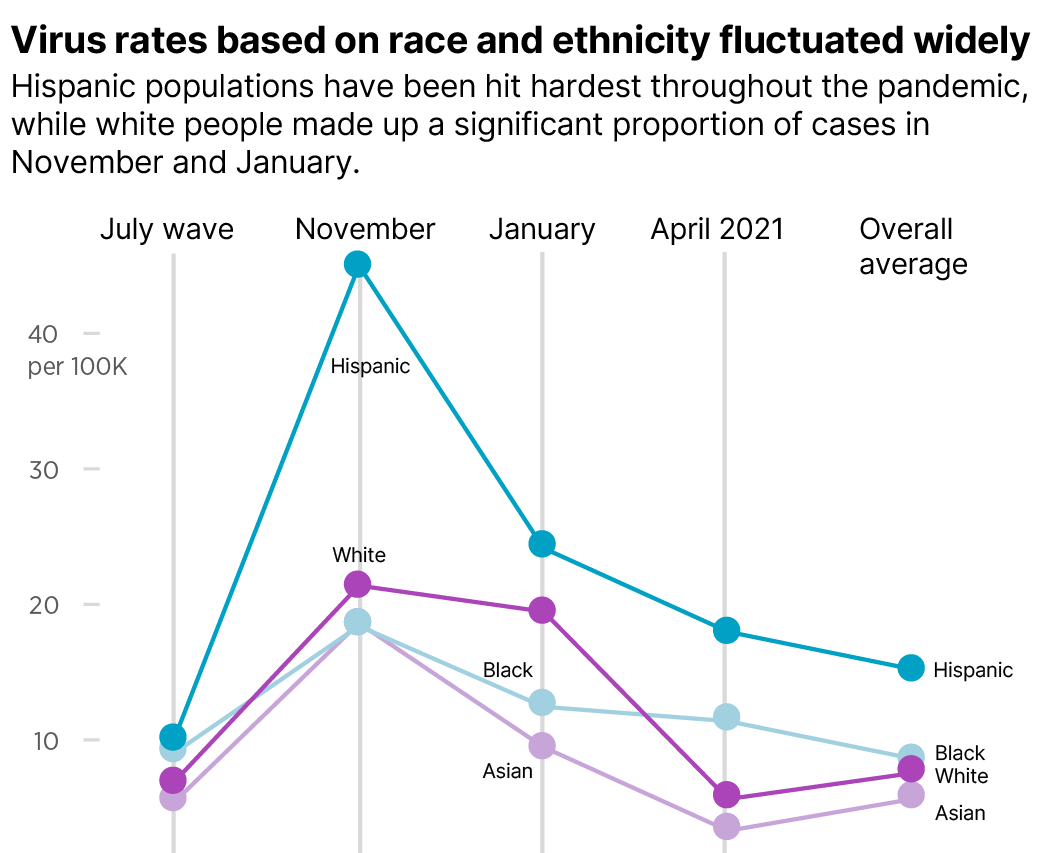

Despite COVID’s recent effects on wealthier counties, minority populations have been the most heavily impacted by the virus and in general suffered worse effects once sick. Hispanic communities have disproportionately high case numbers over the course of every phase of the virus and were more than three times as likely than non-Hispanic white people to contract the virus in July.

The CDC collects and reports demographic data, including race, ethnicity and age on about two thirds of known COVID-19 cases. In order to estimate the COVID impact on demographics such as income and education level, we compared those metrics to case rates in each county. The results show the makeup of the sickest counties, but only approximate the demographics of those who are actually ill in those counties. While almost half of the worst 100 counties in April were located in Michigan, the analysis of demographic patterns held true with or without the inclusion of Michigan counties.

Going forward, demographics will continue to shape who is getting sickest as choices about whether to get the vaccine could be decided along ideological lines. Those differences could come into greater contrast as the remainder of those who are waiting for a vaccine get their turn. In addition to attitudes toward vaccines along demographic lines, access to vaccines has varied by demographic groups. The next steps in vaccination will also depend on increasing access to people who may not have had it.

To learn more about the data behind this article and what Kinsa has to offer, visit https://www.kinsahealth.co/.

Sign up to receive our stories in your inbox.

Data is changing the speed of business. Investors, Corporations, and Governments are buying new, differentiated data to gain visibility make better decisions. Don't fall behind. Let us help.

Sign up to receive our stories in your inbox.

Data is changing the speed of business. Investors, Corporations, and Governments are buying new, differentiated data to gain visibility make better decisions. Don't fall behind. Let us help.