An Urban Exodus or An Urban Shuffle?

One year ago, the outlook for American cities was bleak. The nation’s first major COVID-19 outbreak was coursing through New York City, raising valid concerns about the relationship between disease and density. Anecdotes emerged of New Yorkers taking advantage of newfound remote work flexibility to relocate to other parts of the country to hopefully wait out the worst of the pandemic. Understandably, many predicted a broader “urban exodus” would unfold and drastically alter the future viability of American cities.

In the months that followed, there has been some disagreement over the extent to which this urban exodus materialized. Certainly many households did move this year, and dramatic changes in vacancies and rent prices signal that some suburban areas got more popular while some urban ones became less desirable. But there’s an important byproduct to consider for each family that relocated from San Francisco to Lake Tahoe last summer. Those families created vacancies in San Francisco, something that otherwise takes a lot of time (and money) if done by building new construction.

Those vacancies presented opportunities to new renters, and they are the reason the pandemic will not mark the end of this chapter of urbanization. When urban vacancies pile up the markets respond accordingly with lower prices, which in turn generate interest among newcomers who previously may have been priced out. 2020 was less a story about urban exodus and more of an urban shuffle, whereby the people who left cities will be quickly replaced by the next generation of newcomers. Search data from the Apartment List platform show this happening: as cities lost residents they gained the attention of new prospective renters that will sustain them going forward.

Will Renters Move To More of Less Dense Cities?

Despite anecdotal stories of urban flight, the majority of big city renters looking for a new apartment during the pandemic were not rapidly abandoning their hometowns. As the pandemic accelerated in the spring and summer, 62 percent of all searches on Apartment List were “out-of-town” searches - users living in one city but searching for homes in another. This is actually slightly lower than previous, pre-pandemic years.

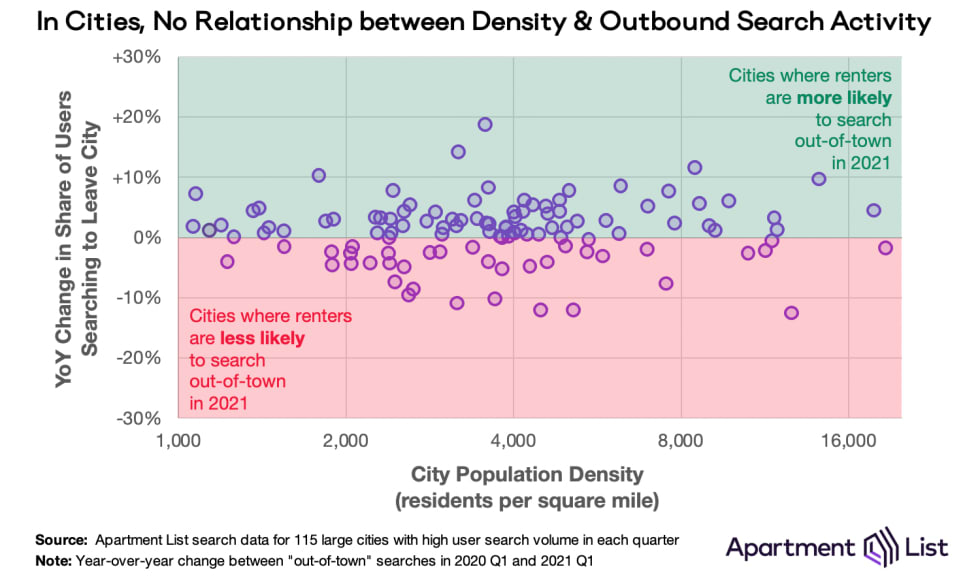

An urban exodus story would predict that out-of-town searches grew and clustered in dense, urban areas. But Apartment List data show no such relationship. In the chart below, each point represents a large city; on the x-axis is the city’s population density, and on the y-axis is the percentage point change in the frequency of outbound “out-of-town” searches. Points in the green zone are cities where renters have become more inclined to look beyond city limits in 2021; points in the red zone are cities where renters are more likely to search locally. Density and likelihood of searching in a new region are uncorrelated. And in six of the ten densest cities (those with more than 10,000 residents per square mile), renters were actually less likely to be searching out-of-town in the first quarter of 2021 compared to 2020.

The vertical range of these data points suggest a good deal of regional variation. In other words, apartment seekers in some cities are more localized this year, while in others they are more eager to move somewhere new. Yet there is no discernable widespread pattern to indicate that going forward dense cities will shed residents at a faster rate than others.

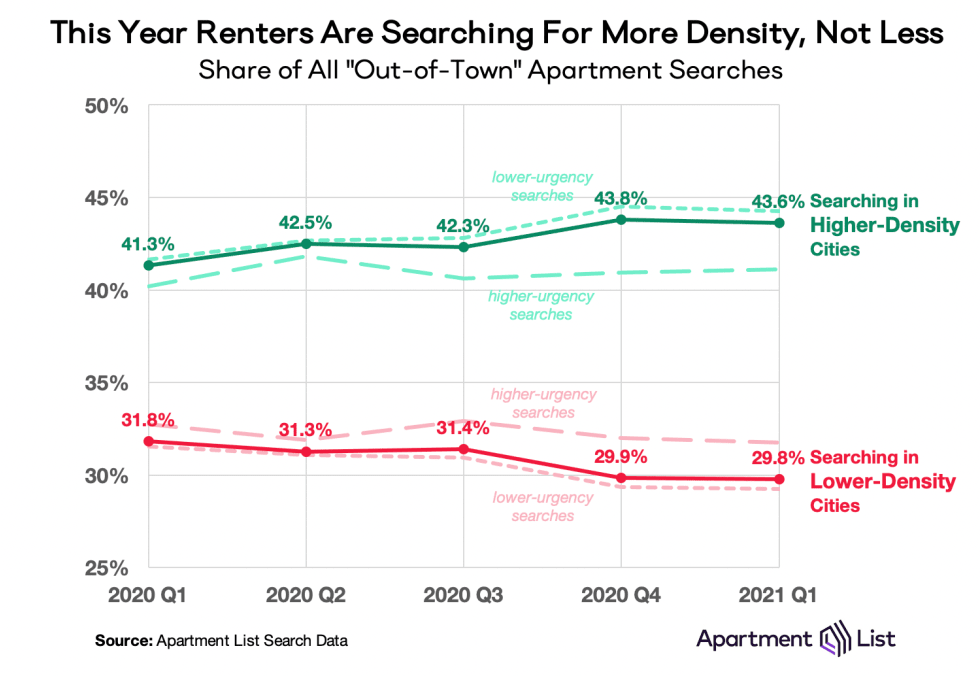

Meanwhile, despite the supposed stigma against density, those who are looking to change cities are increasingly searching for more density, not less. Every search on Apartment List contains a pair of cities: the city that the user is searching to and the city they are searching from. In the first quarter of 2020, 41 percent of out-of-city searches were for places that are at least 25 percent more dense than the renter’s home city. One year later, that share has ticked up slightly to 44 percent. Conversely, the share of searches for lower-density cities (at least 25 percent less dense) has dipped from 32 percent in 2020 Q1 to 30 percent a year later.

As an online rental marketplace, some renters come to Apartment List in urgent need of a new home while others search casually without a strict timeline. We can segment users into higher- and lower-urgency groups, which further demonstrates how in the face of a pandemic, rent drops were a successful catalyst for search interest into denser cities. Higher-density search activity is driven by the lower-urgency group, in other words, renters who are in the early stages of moving or simply browsing. These renters may have never considered a move to a denser, more expensive city before their price declines made headlines.

Are Renters Dispersing From or Concentrating Within Metro Areas?

Another way of looking at the pandemic’s impact on urbanization is to examine how renters are searching for homes within each metropolitan area. Because even in lower-density parts of the country, metropolitan areas consist of a higher-density urban core (i.e., a “principal city”) surrounded by lower-density suburbs (i.e., “secondary cities”). Hundreds of principal cities exist across the country, and even those that are not objectively dense retain many urban amenities like walkable neighborhoods, public transit systems, restaurants, museums, and cultural spaces.

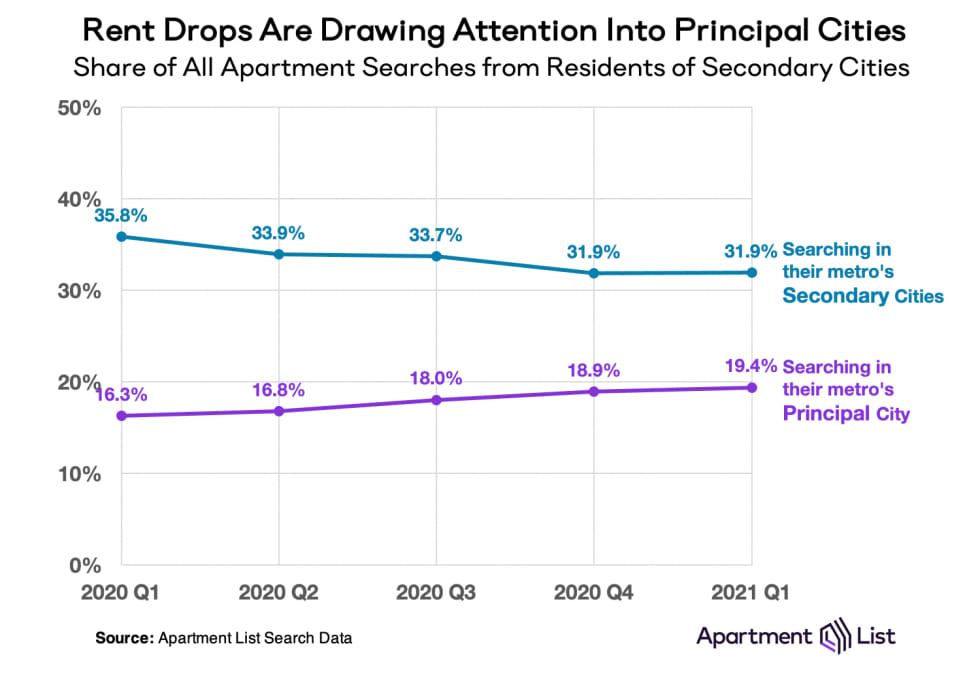

In 2020, rents fell in principal cities while staying relatively stable in secondary ones. This is most often attributed to lower apartment demand: in 2020 some renters left principal cities while others never showed up. And with fewer people competing to sign leases, rent dropped. But these rent drops are more than just a response to low demand, they are also a self-correcting mechanism to generate new demand. So while some interpreted 2020 as a year in which principal cities grew weaker, Apartment List data show that cheaper rents actually increased the attention they received from prospective renters in surrounding secondary cities.

To illustrate this, we can take the nation’s 100 largest metropolitan areas and divide each into its principal and secondary cities. Following the pandemic, renters living in secondary cities show more signs of an urban concentration than an urban exodus. Throughout the pandemic, secondary-to-principal searches grew in popularity, gradually increasing from 16 percent in 2020 Q1 to 19 percent in 2021 Q1. All the while, searches within other secondary cities fell from 36 percent in 2020 Q1 to 32 percent one year later. This trend indicates that steeply falling rents in many principal cities are piquing the interest of residents in secondary cities who may have previously considered downtown rents to be out of reach.

And among those living in principal cities, the vast majority continue to be most interested in apartment hunting locally. In the three months preceding the pandemic, the majority (66 percent) were searching for their next home in their current city while just 15 percent were searching in one of their local secondary suburbs. The pandemic did not disrupt this pattern; even as the most severe economic disruptions unfolded, secondary search interest declined slightly to 13 percent in the first quarter of 2021.

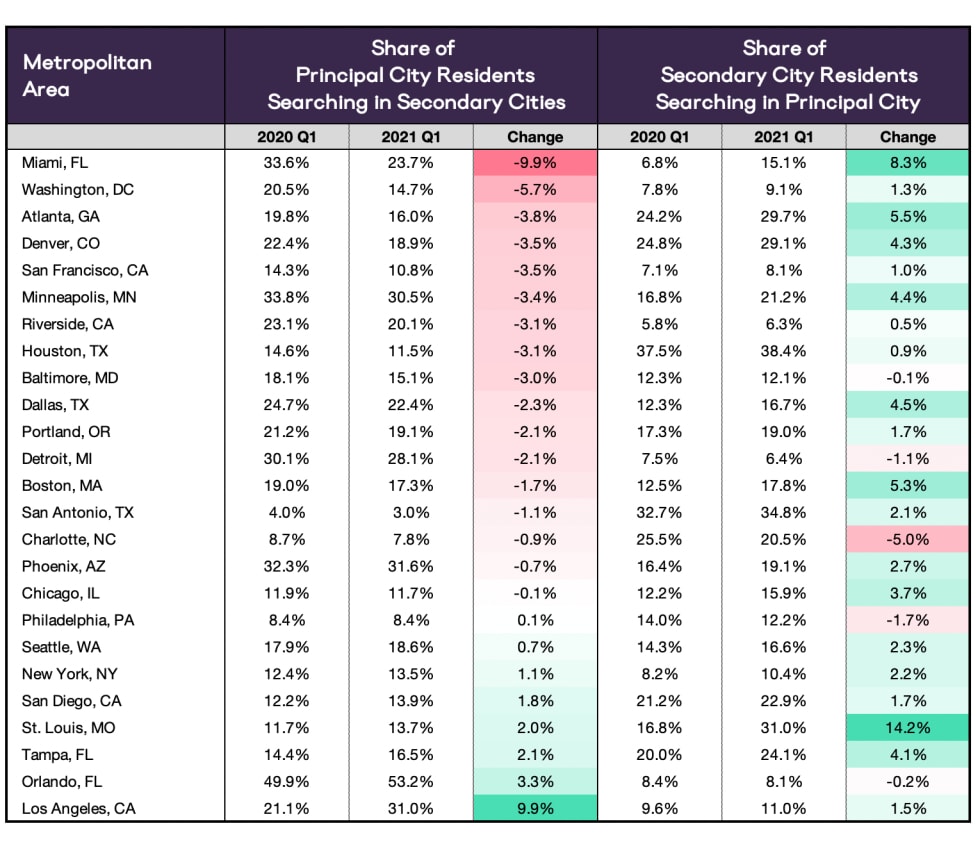

These “urban concentration” search trends hold true in many of the nation’s major metropolitan areas. Among the 25 largest, principal-to-secondary searches dropped in 17 while secondary-to-principal searches rose in 20. Miami metro saw the largest year-over-year concentration: a near-double-digit drop in the rate of principal-to-secondary searches while searches in the other direction more than doubled.

Are Renters Making Permanent or Temporary Moves?

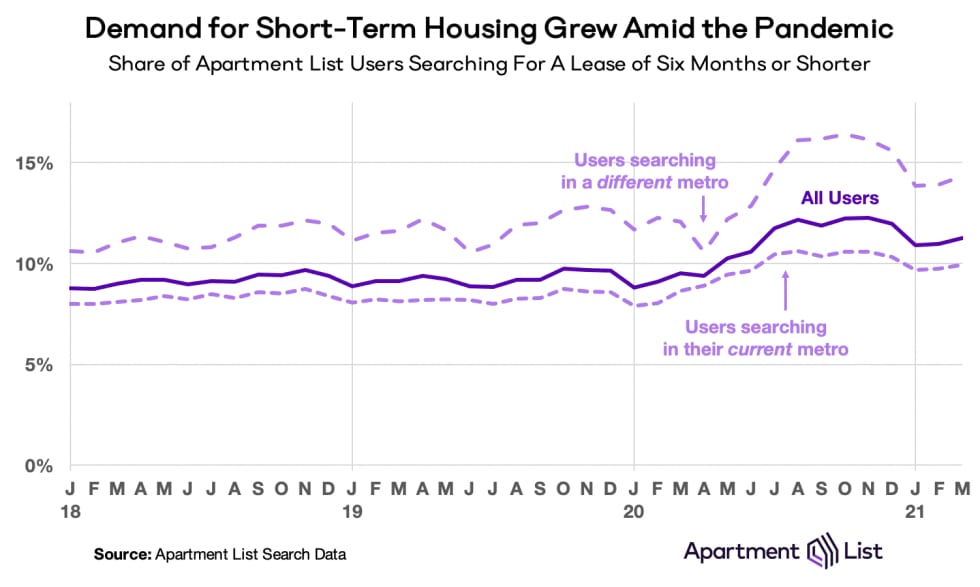

In last quarter’s renter migration report, we shed light on a new pandemic-era trend: increased demand for short-term leases that span six months or fewer. Pre-pandemic, roughly nine percent of all Apartment List users requested short lease terms; then starting in April 2020 and continuing steadily through the end of the year, demand rose. The trend receded a bit in the first quarter of 2021 but has settled at a new baseline that is higher than the same time last year.

Those who sign short-term leases are signalling a lower level of commitment to staying in their next home. There are a number of ways in which the uncertainty of the pandemic may have driven increased demand for short-term leases. While it has always been higher for those looking to move to a new city or metro compared to those searching within their existing city, that gap has widened as the pandemic persisted. We also see a big jump in short-term lease demand among those looking to move to lower-density cities. These trends may signal that the pandemic changed some renters’ location preferences, but only temporarily.

It also tells us that some renters who decided to “wait out” the pandemic in a new city were planning to move back once the threat of the virus subsided. Others may be wary of making a long-term commitment to a new city that they are not familiar with. Still others may be interested in taking advantage of new remote flexibility to experiment with life as a “digital nomad,” hopping from place to place for short stints of time. And even among those who are not moving to a new city, rapid price fluctuations could be making some renters hesitant about locking in a price for a full year if they anticipate that their market will cool in the months after they sign a lease.

Conclusion

Over the past year, there has been significant speculation about what the pandemic would mean for the future of cities. Predictions of urban exodus felt intuitive, given that social distancing requirements put a pause on many of the activities that make city life vibrant, while at the same time, remote work had freed many Americans from needing to live close to their jobs. Despite this narrative, our search data show that big, dense cities are maintaining their allure even as some residents move away

Renters who did move created high-demand vacancies that are attracting a lot of attention. As the pandemic continues, renters looking to move someplace new have grown increasinging likely to be searching in a location that is more dense than where they currently live. Those living in the core cities of major metro areas have become slightly more likely to want to stay put, while at the same time, renters living in the suburbs have grown more likely to be searching downtown. If the pandemic is pushing people out of cities, it is also opening doors for new ones to enter.

It is important to keep in mind that these data reflect search activity rather than complete moves, but we see clear evidence that interest in big cities has not waned. While it is true that plummeting rents in some expensive cities have signalled shifting demand for these locations over the past year, these price corrections seem to be succeeding in drawing new interest, such that these cities are not hollowing out. Even there, our most recent rent estimates are showing a rebound in demand for dense urban living. And while remote work still has the potential to reshape housing markets, the long-term impacts are likely to play out gradually, and are unlikely to represent a death knell for big cities. All in all, the “urban exodus” narrative seems to be one that we can close the door on.

To learn more about the data behind this article and what Apartment List has to offer, visit https://www.apartmentlist.com/.

Sign up to receive our stories in your inbox.

Data is changing the speed of business. Investors, Corporations, and Governments are buying new, differentiated data to gain visibility make better decisions. Don't fall behind. Let us help.

Sign up to receive our stories in your inbox.

Data is changing the speed of business. Investors, Corporations, and Governments are buying new, differentiated data to gain visibility make better decisions. Don't fall behind. Let us help.